New evidence on online child sexual exploitation and abuse is crucial in informing how we can best tackle this evolving threat. In response to this gap, UNICEF Office of Research – Innocenti, INTERPOL and ECPAT International initiated in 2019 the Disrupting Harm research project, with financial support from the End Violence Fund. Together, we set out to bridge the gap in national and global evidence of OCSEA. Our aim was to better understand the scope and nature of OCSEA and to assess how well national systems were responding to this crime.

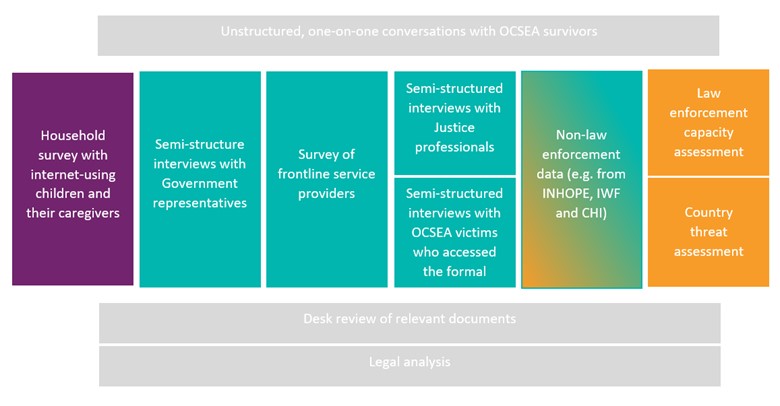

The research was conducted from 2019 to 2022 in six countries in East Asia Pacific (Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam) and seven countries in Eastern and Southern Africa (Ethiopia, Kenya, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda). Through the nine research activities shown below, each Disrupting Harm national assessment engaged children, policymakers, justice representatives, law enforcement and others to collect comprehensive data on OCSEA. All the data were triangulated and made available in the Disrupting Harm national reports.

Figure 1: Disrupting Harm research activities

Here we present primarily data from internet-using 12-17-year-olds who took part in a nationally representative household survey. The survey questionnaire used for Disrupting Harm was adapted from the Global Kids Online survey, which has already been used in over 30 countries around the globe. Additional modules were developed specifically for the Disrupting Harm project that focused on children’s experiences of different forms of violence, including OCSEA.

The scope of online child sexual exploitation and abuse

We used various indicators in this survey to measure online sexual exploitation and abuse of children:

- Someone offered you money or gifts online in return for sexual images or videos;

- Someone offered you money or gifts to meet them in person to do something sexual;

- Someone shared sexual images of you without your consent;

- Someone threatened or blackmailed you online to engage in sexual activities.

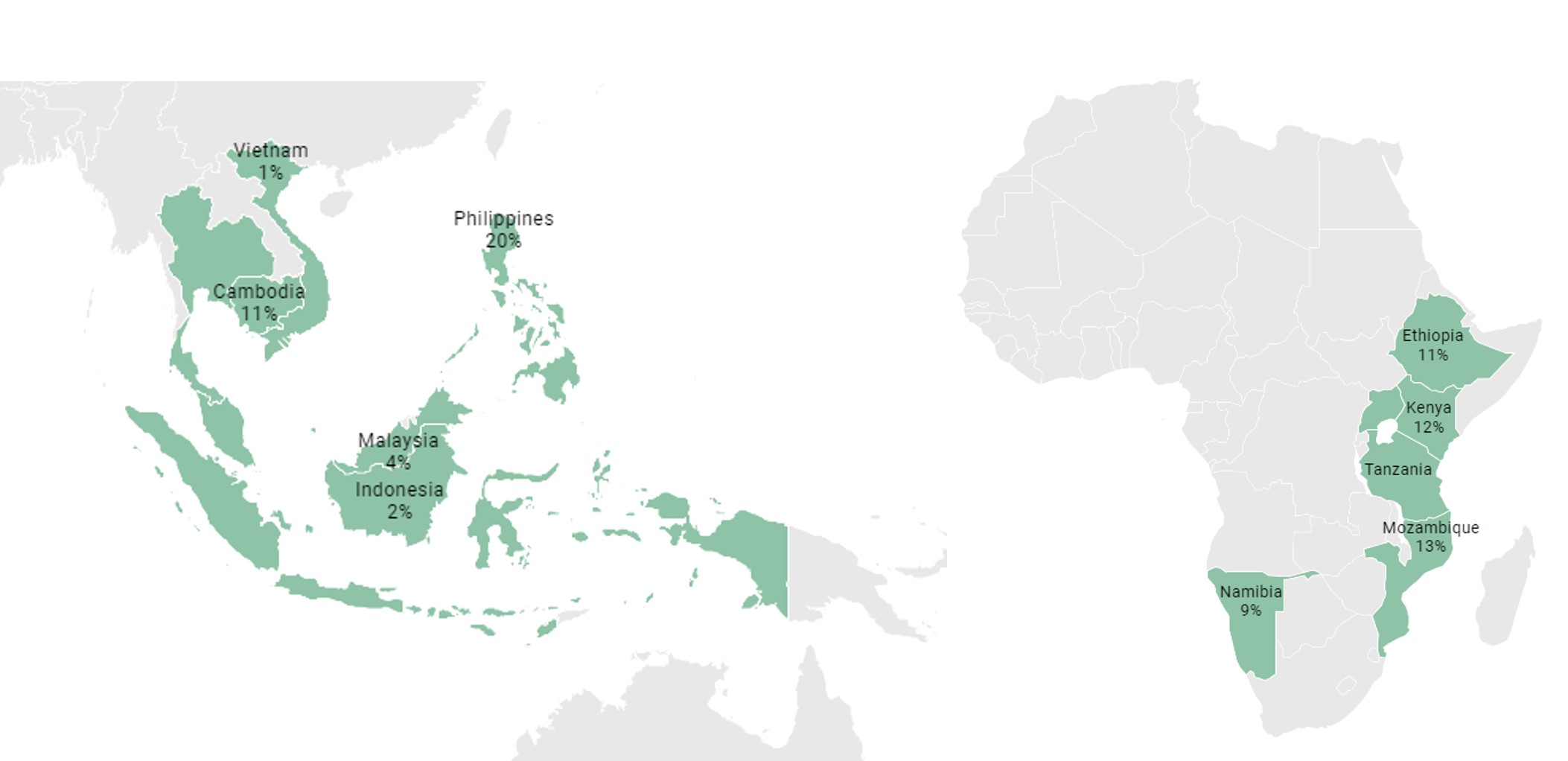

According to the children surveyed across 12 countries,[1] anywhere between 1 – 20% were subjected to at least one of these forms of online sexual exploitation and abuse in the past year alone.

Figure 2: OCSEA in 12 Disrupting Harm study countries

There is a connection between online and offline sexual exploitation and abuse

While each country is unique in terms of children’s experiences of OCSEA and how the national systems are responding, consistent findings emerged across countries. Sexual exploitation and abuse can occur online while a child is using the internet but technology can also be misused to facilitate in-person sexual abuse. For example, a child might be targeted and groomed via social media and later coerced to meet the offender in person, where contact sexual abuse occurs. Another example is where technology is used to livestream contact sexual abuse.

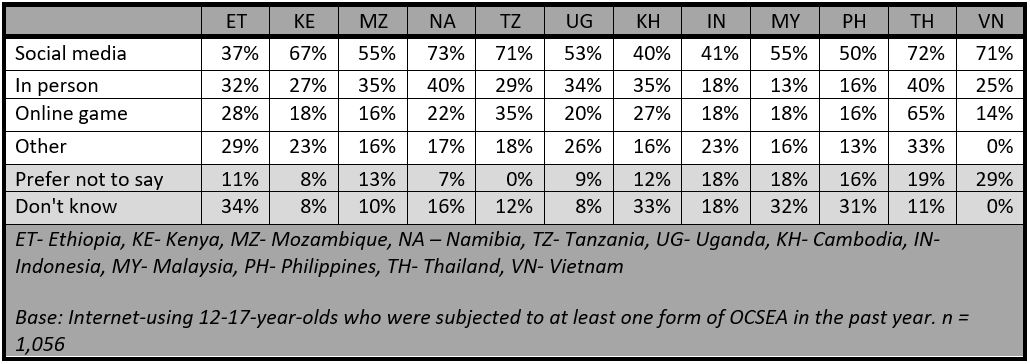

In many countries where we collected this data, children were most likely to be subjected to OCSEA through social media. Children in all 12 countries were most often targeted via Facebook/Facebook Messenger or on WhatsApp. But in many countries, more than a third of these experiences happened in person (see Table 1), illustrating how intertwined ‘online’ and ‘offline’ sexual abuse can be. Analysis conducted by the Disrupting Harm team for a forthcoming publication shows that most children who have experienced online sexual exploitation and abuse have also experienced sexual violence in person.

Table 1: Where do children experience online sexual exploitation and abuse?

Offenders tend to be known to the child

Despite a widespread concern that ‘strangers’ are the biggest threat to children online, children in all countries except the Philippines said that offenders were most often people they already knew. This has implications for prevention and awareness-raising efforts – children, caregivers and the general public need a better understanding that child sexual exploitation and abuse comes from both strangers and people the child already knows. Prevention and support programmes should take into account that victims can be emotionally and financially dependent on their abusers which further complicates disclosure.

Children struggle to disclose their experiences and seek help

Overall, children reported high levels of perceived support from their immediate circles: almost all children (91%) said that they could turn to their family for help and two-thirds (65%) would talk to their friends if they had a problem. However, the reality of help-seeking is quite different. Around one-third of children subjected to OCSEA did not tell anyone what happened to them.

When children disclosed their abuse, they most often told a peer. Almost half of children who disclosed their abuse turned to a friend and around one in four – to a sibling. It was less common for children to confide in adults, including female or male caregivers. By far the least common route to support was via social workers, helplines or law enforcement. Only very few children who experienced OCSEA reported their case to the police.

This raises the question of why children are often uncomfortable disclosing these experiences to adults. A recently published Disrupting Harm brief presenting insights from survivors of OCSEA shows that the most common barriers to disclosure and reporting were not knowing where to go or whom to tell and feeling too embarrassed to discuss the situation. This suggests that pathways to support need to include raising awareness of what OCSEA is, improving knowledge of existing reporting mechanisms and possibly developing new ones that work better for children, as well as helping children to overcome their reluctance to disclose sexual abuse and seek support.

Moving forward

Based on the new evidence, how can we prevent the harm of online child sexual exploitation and abuse? Each Disrupting Harm country report recommends extensive steps for Governments and other national stakeholders to better prevent and respond. Some of those recommendations include:

1. Educate the public about violence against children (including OCSEA), how to spot it, who the likely offenders are, and how to seek support. Awareness campaigns should be evidence-based and should always be created in consultation with children and other relevant stakeholders. Reporting and support mechanisms should be improved based on discussions and recommendations of children.

2. Engage with children in age- and development-appropriate conversations about topics such as consent, personal boundaries, and risky online activities like sharing sexual images. When children do not know about these things, it enables offenders to take advantage.

3. Coordinate across programmes focused on ‘online’ and ‘offline’ sexual violence and, to the extent that it makes sense, across programmes focusing on violence against women and children.

4. Train police officers about the overlaps between online and in-person forms of CSEA, inform them about the provisions of law that can be used to bring charges in cases, and ensure they liaise with child protection services as needed.

5. National law enforcement and social media platforms should liaise more closely and build on existing collaborative mechanisms if they are available. This is one step to ensure that digital evidence needed in OCSEA cases can be gathered rapidly and efficiently, that data requests are quickly resolved, and that illegal content is promptly removed.

6. Facilitate reporting. Recognize that children predominantly turn to their friends or siblings to disclose abuse. There is a need to increase efforts to improve trust between children and adults. In parallel, ensure that children are aware of the various reporting channels available to them, and how to make a report. Organizations that receive reports have a duty to ensure that they are acted upon expediently.

Additional resource

Disrupting Harm country reports

Lessons learned and promising practices to end OCSEA in low and middle income countries

Legislating for the digital age

Pathways from offline to online risk

Children’s vulnerabilities and protective factors

The impact of Globa Kids Online

[1] A nationally representative survey was also conducted in South Africa, however that data is not included here because variables required for this analysis were not collected.

Authors: Daniel Kardefelt-Winther and Marium Saeed