Patricio Cabello from Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaiso and Magdalena Claro from the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile presented the findings from the nationally representative survey of 1,000 children aged 9 to 17 years and their parents. The study covered the 15 regional districts in Chile and involved face to face computer-assisted personal interviews (CAPI) at children’s homes.

Patricio Cabello from Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaiso and Magdalena Claro from the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile presented the findings from the nationally representative survey of 1,000 children aged 9 to 17 years and their parents. The study covered the 15 regional districts in Chile and involved face to face computer-assisted personal interviews (CAPI) at children’s homes.

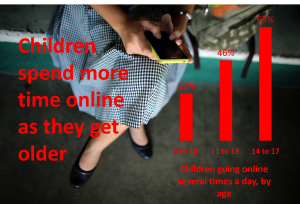

The study found that almost all children, regardless of their socio-economic background, go online using a smartphone (92%). As they get older, children spend more time online. While over a quarter of the 9 to 10 year olds go online several times a day, this proportion increases to almost two-thirds of the 14 to 17 year olds. Children go online more during the weekend – about half of the children surf the internet for 5 hours or more on Saturday or Sunday. Children who are less well-off spend less time online than their peers on a week day but almost the same time online during the weekend. Girls spend more time online than boys but also use the internet for studying more than their male peers.

Even though only a small proportion of children (6%) don’t use the internet at home, about a third of children do not use the internet at school (34%). Nevertheless, the internet offers a lot of learning opportunities to children in Chile. Most of the children (84%) have used the internet during the last month to do homework and every two in three children say that they have learned something new. Over a quarter have also used the internet to look for information regarding job or study opportunities and even more children (40%) have looked for health information or read the news (36%).

Many children also go online for entertainment or socialising. The most popular activities are: watching videos (91%), chatting (81%), using a social network (73%), playing games (69%), sharing photos, videos or music (59%), and talking to family or friends who live far away (54%). Civic and creative activities are less prevalent, but still almost a quarter of children use the internet to learn about their neighbourhood, talk to people from other cities or countries, or participate in a site where people share their interests or hobbies.

Most of the children report having a wide range of digital skills but younger children and those from poorer backgrounds are less skilled. Overall, the majority of children know how to install apps on a mobile device (84%), delete people from their contact list (74%), save a picture they found online (67%), choose the right search words (67%), or know which information they should or should not share online (67%). The most challenging areas with the lowest proportion of children reporting that they know how to do these activities (about a third) are: keeping track of the costs of the mobile applications, recognizing the different types of internet licenses, or being able to upload videos or music that they created.

Most of the children in Chile do not report facing online risks or engaging in risky behaviours. Most do not send personal information (e.g. full name, address, or phone number), a photo or a video of themselves to people they don’t personally know – still 14% have sent personal information and 8% photos or videos. Again, the majority of children do not pretend to be someone else (only 8% have done this) and they do not add unknown people to friends or contacts lists – still about 1 in 5 children (24%) have added strangers.

Most of the children in Chile do not report facing online risks or engaging in risky behaviours. Most do not send personal information (e.g. full name, address, or phone number), a photo or a video of themselves to people they don’t personally know – still 14% have sent personal information and 8% photos or videos. Again, the majority of children do not pretend to be someone else (only 8% have done this) and they do not add unknown people to friends or contacts lists – still about 1 in 5 children (24%) have added strangers.

Over half of the children (59%) never experience anything upsetting online and further 24% have such negative experiences only once or twice a year. Twelve percent of children, however, see or experience something upsetting online at least monthly or more often (and 6% do not know or prefer not to say).

Only half of the children who experience something negative online seek help. Still between a fifth and a third of children say that their parents never or hardly ever talk to them about what to do when something upsetting happens (39%), about internet safety (22%), or negative online content (26%). Similar proportions of children are not encouraged by their parents to explore the internet (35%), they are not offered help to find things online (29%), nor do their parents talk to them about what they do online (29%) or stay around when the child uses the internet (29%).

Speaking about the new findings, Patricio Cabello emphasised:

“We found that 36% of children and adolescents had at least one upsetting experience online, for most of them it was just once or twice in a year. Those who encounter negative experiences frequently are only a small proportion. This is an interesting finding in our context where parents and media seem very worried about negative online experiences, while online opportunities, digital skills and positive experiences receive less attention. Now we know more about the complexity of a range of online behaviors, for example how parents mediate and support children’s online activities, and how children perceive such mediation.”

Magdalena Claro adds:

“These results are relevant to social and educational policies in Chile, since they show that, although children are increasingly having access to digital technologies, the quality of this access and the skills they have to benefit from this use are shaped by their family’s social, economic and cultural background. Participating and benefiting from digital opportunities requires digital skills that the education system should develop in every student: but if one third of the children who are internet users in Chile report never using the Internet at school, it is clear that this is not happening.”

Sonia Livingstone, who was a keynote speaker at the launch event, put the new findings from the Chilean research into the context of Children’s rights in the digital age: present paradoxes and future promise. In her talk, she suggested that, to understand how children’s rights are being reconfigured in and through digital networks and services, a series of problems and paradoxes need to be resolved: first, the problem of ensuring rights online as well as offline; second, the problem of prioritising among potentially clashing rights; third, the problem of distinguishing opportunities from risks; last, the problem of identifying the best interests of the child online.

Download the presentation with findings

You can sign up to receive the latest research news from Global Kids Online by email. Please forward this message to anyone you think may be interested.

Post author: Mariya Stoilova