The new report launched today shows that children in Zambia are using the internet for learning, chatting, listening to music, streaming videos, watching their favourite influencers, and playing the same games as so many children online everywhere: Minecraft, Warcraft, Call of Duty, Clash of Clans, Candy Crush and FIFA.

The new report launched today shows that children in Zambia are using the internet for learning, chatting, listening to music, streaming videos, watching their favourite influencers, and playing the same games as so many children online everywhere: Minecraft, Warcraft, Call of Duty, Clash of Clans, Candy Crush and FIFA.

Online experiences of risk

Yet as children in Zambia leap into the wealth of content that exists online, with little support from adults around them, they are ill-prepared for the potentially harmful content that they might encounter and have little in the way of resources to support them when they do come across problematic content or behaviour online.

While children in Zambia are clearly encountering contact risks, they are facing conduct (and content) risks even more frequently. In some cases, they are actively seeking out content that could potentially result in harm. Many of the topics that they explore online are often ‘invisible’ or taboo to talk about in their homes, schools or communities, and so children have no means to process the information that they see.

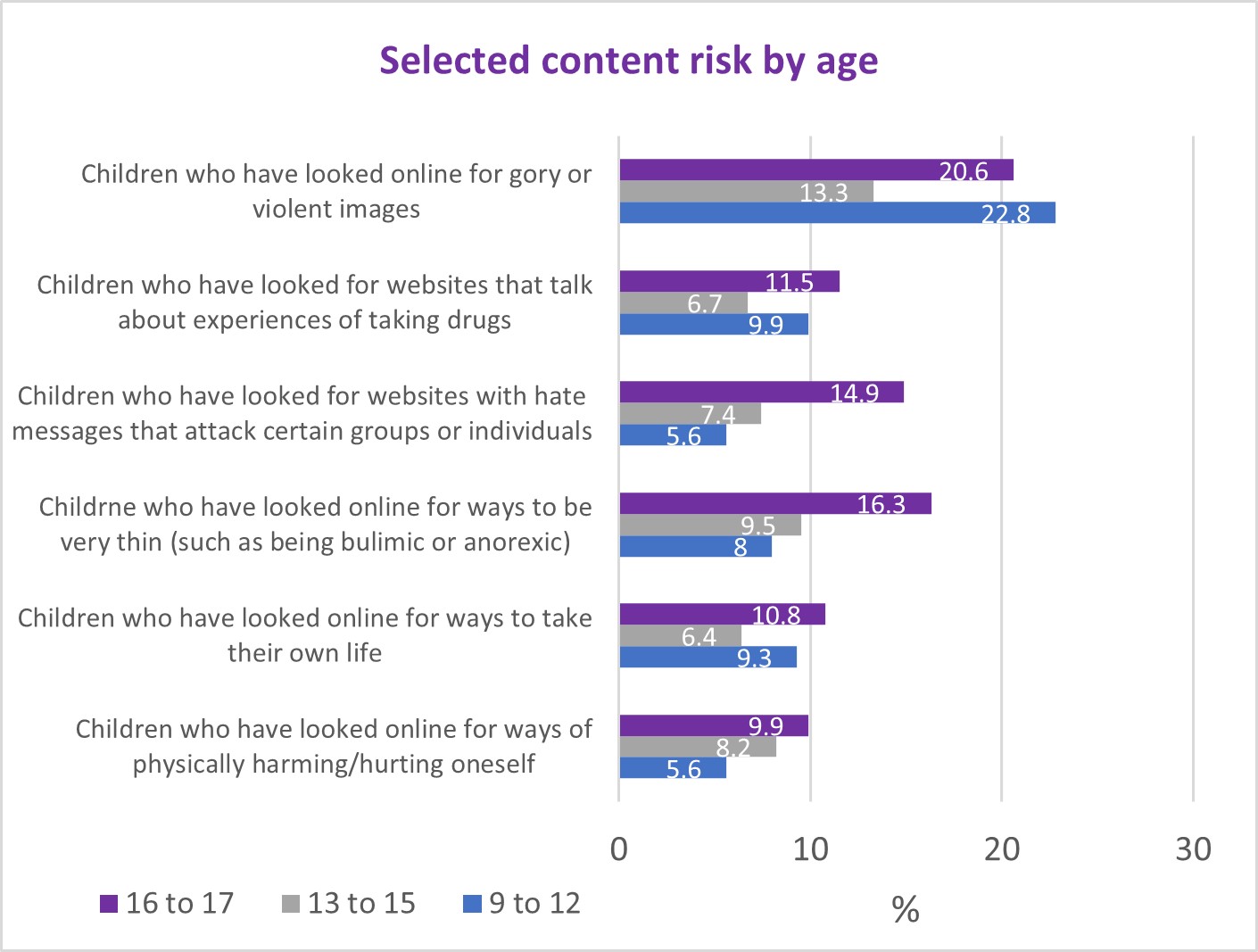

This is particularly concerning given the age at which children are starting to encounter potentially harmful content, such as discussing or promoting self-harm, suicide and eating disorders. While the contact risks reported by children through both the survey and focus group discussions were experienced predominantly by older children, many of the content risks are faced by children as young as nine or ten years old.

The study found that 9% of children had actively looked for websites with information on how to take their own life. Almost one in ten (9%) children aged 9 to 12 years had actively sought out information on how to harm themselves, compared to 6% of children aged 13 to 15, and 11% of children aged 16 to 17. Similarly, one in ten children aged 9 to 12 had actively sought out information online on taking drugs, and 8% had sought out websites on ways to be thin, on bulimia or anorexia.

There was little difference in the experiences of boys and girls, with the exception of those who sought out information on eating disorders, where 14% of girls compared to 10% of boys reported looking for such content.

Help-seeking and support

Children’s limited awareness and knowledge of the online risks is linked to another important gap – that of help-seeking. Many parents or caregivers do not even know that their children are accessing the internet as children sometimes go online outside the home, rather than using their own device or borrowing one from their parents. Children in Zambia report feeling nervous that their teacher or parent will restrict their internet access if they find out about their online activities and experiences, so they prefer not to tell them.

In most cases when children in Zambia are bothered by online experiences, they do not tell anyone about it. When they do speak to someone, it is most commonly a friend or an older sibling. So, children are largely figuring out their way online without the support of caregivers, teachers, or any responsible adult in their life, which increases the risk that they might experience harm. At the same time, children are also sharing strategies amongst themselves to try and mitigate these risks.

When children are encountering, and indeed actively seeking out, age-inappropriate and potentially harmful content, support networks for the child are critical. Yet, there is little evidence in the data that children are aware of, or have in place, adequate support mechanisms to turn to when facing challenges and difficulties in their life, either online or offline, or when environmental and experiential factors are catalysing the exploration of this content. There is little in the way of formal systems or resources available to guide or support children in Zambia who are experiencing risks online. Even more importantly, the opportunities to identify and intervene with children at risk who may be more vulnerable to the harms associated with such content are limited.

This suggests that there is a need to develop better early intervention and prevention mechanisms to identify and support children who may be at risk. From a response perspective, this data also highlights the importance of integrating children’s online lives and experiences into broader child protection and case management systems, to ensure that systemic responses to support and respond to harms resulting from online activities are available and adequately equipped and resourced.

Zambia is amongst the few countries within the region that has a Child Online Protection Strategy. This provides an important departure point for actions to be taken by the government, industry and others to ensure that children stay safe online. Importantly, the Strategy calls for

periodic studies on COP that will among other things include age and gender disaggregated evidence on Zambian children’s online activities, risks and opportunities (Ch 5. Obj 2. Pg.20)

The Zambia Kids Online study responds to this call, albeit partially as it was limited to three sites rather than being national. While not representative of all children in Zambia, the data provides a cross-sectional snapshot of children’s online activities and experiences and already points to a number of practical intervention areas, and potential policy gaps, that can be addressed in order to foster an empowering, safe online environment and experience for children in Zambia.

The Zambia Kids Online study was undertaken by the Zambia Institute for Policy and Research (ZIPAR), for Save the Children Zambia and Lifeline Childline Zambia, with support from Save the Children Finland, and was funded by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Finland. The study collected data from a randomized household sample of 988 children from nine to 17 years old (531 girls and 457 boys) and 999 parents (717 female and 282 male carers) in three peri-urban sites in Zambia.

The full report was launched on the 10th May 2022 in Lusaka by the Save the Children’s Child Rights Resource Centre.

About the authors

Patrick Burton is a research consultant working with Save the Children Zambia and UNICEF in Zimbabwe, Albania and South Africa, as well as the Executive Director of the Centre for Justice and Crime Prevention. Together with his co-PI Dr Monica Bulger, he won the Best of UNICEF Research award in 2020 for their work on Children’s use of social media in East Asia.

Miselo Bwalya is a trained economist and researcher working as Policy Researcher and as a Research Fellow with the Human Development Unit of the Zambian Institute for Policy Analysis and Research (ZIPAR). His research interests are in understanding the various forms of poverty and how they manifest in labour, financial inclusion, social protection and education.