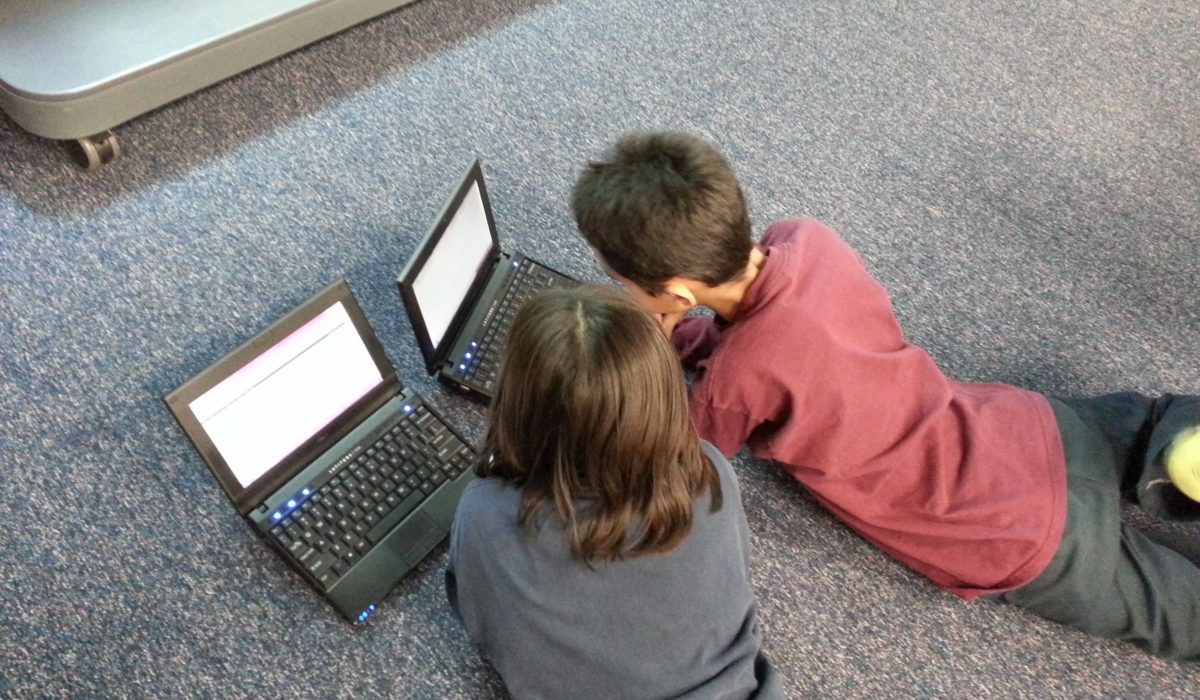

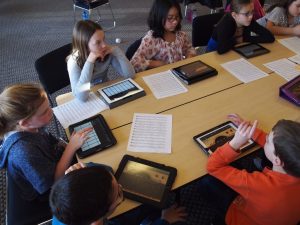

The Canadian Kids Online project will investigate young Canadian’s experiences in online environments. Specifically, it will explore the ways in which the online environment can amplify risks, as well as opportunities for young Internet users, and how their attitudes and sensitivities towards privacy issues relate to the risks and opportunities that they experience. This project will carry forward previous research that eQuality conducted with MediaSmarts which focused on teen’s privacy decisions surrounding the posting and sharing of photos on social media, as well as eQuality’s Law Commission of Ontario-funded research into teen’s attitudes towards online defamation. The Canadian Kids Online survey, will help to further our understanding of youth attitudes towards online privacy and the ways in which privacy decisions shape their experiences online.

The Canadian Kids Online project will investigate young Canadian’s experiences in online environments. Specifically, it will explore the ways in which the online environment can amplify risks, as well as opportunities for young Internet users, and how their attitudes and sensitivities towards privacy issues relate to the risks and opportunities that they experience. This project will carry forward previous research that eQuality conducted with MediaSmarts which focused on teen’s privacy decisions surrounding the posting and sharing of photos on social media, as well as eQuality’s Law Commission of Ontario-funded research into teen’s attitudes towards online defamation. The Canadian Kids Online survey, will help to further our understanding of youth attitudes towards online privacy and the ways in which privacy decisions shape their experiences online.

Teens’ privacy decisions

This past year, eQuality partnered with MediaSmarts to explore how Canadian youth make privacy decisions about the sharing of photos on social media platforms. We recruited 18 teenagers between the ages of 13-16 and asked them to complete photo-diaries for seven days over two weeks – limited to three photos per day over any five school days and two weekend days over a 14 day period, using three photo categories: comfortable sharing with many people; comfortable sharing with a few people; and, not comfortable sharing with anyone. Each participant was then interviewed by a researcher to discuss their choices with respect to which photos they shared and why.

Despite the rhetoric around selfie-culture, we found that our research participants were far more likely to share a photo without any people in it because they did not want to open themselves, their friends, or family up for judgment (group shots with many individuals were favoured for the same reason). Interestingly, sharing photos was less about expressing themselves and more about sharing content that was appealing to “everyone”. For example, one participant posted photos of horses on her Instagram, not because she likes horses, but because they made a good “theme” that appealed to “followers”.

We discovered that these photos take on a transactional quality, as they are designed to provide evidence that the poster meets the status quo (with success being measured in likes and comments). Interestingly, these transactional photos were only maintained for their notional audiences. For connecting with close friends, the participants relied on me

dia such as instant messaging or texting because the “private” nature of these platforms allows them to relax and be themselves.

Young people’s attitudes towards online defamation

As part of eQuality, we also recently completed a project funded by the Law Commission of Ontario on Defamation Law in the Age of the internet, which focused on young Canadians’ perspectives on defamation. We interviewed 20 participants between the ages of 15-21 concerning their experiences with truth and falsity, reputation, anonymity, and the quality and utility of existing mechanisms for responding to defamatory attacks online.

We received a ringing endorsement of the importance of privacy, as well as privacy protections to support the transparent management and protection of users’ privacy. Further, informational control was seen as essential to the ability to build different reputations for different online audiences. Participants noted that their differing self-presentations were often driven by a desire to satisfy the requirements of the various social media platforms. For example: LinkedIn profiles tended to be professional; Instagram profiles were “artsy”; and Facebook profiles tended to be more “family oriented.” In addition, participants’ construction of different profiles was often driven by a desire to protect other important rights such as equality and free expression.

Participants felt that while untrue statements can hurt a person’s reputation, true statements that violate confidentiality and privacy could be just as harmful. The true but harmful situations described by our participants often involved non-consensual disclosure of intimate images.

Overall our participants indicated that young people targeted by online attacks prefer responses that maintain privacy and confidentiality, while preserving transparency and accountability, except in the most extreme cases, such as those involving racism and sexual violence, where legal responses were seen by some to be appropriate.

eQuality is now looking forward to building on this research and carrying forward the lessons learned into the Canadian Kids Online project. By learning more about the youth’s privacy decisions and their experiences in the online environment, we will be better placed to contribute to global comparative analysis, and to inform evidence-based policies and international standards that ensure that the online environment is a safe and positive space for everyone. The Canadian Kids Online project will be launched in Ontario in 2018, and results will be published in early 2019.

Further Resources:

To Share or Not to Share: How Teen’s Make Privacy Decisions About Photos on Social Media

Defamation Law in the Age of the Internet: Young People’s Perspectives

Post author: Robert Porter, University of Ottawa

You can sign up to receive the latest research news from Global Kids Online by email. Please forward this message to anyone you think may be interested.