Since the advent of widespread access to the internet and mobile phones, there has been growing concern over hurtful online behaviour among children and young people, which happens alongside face-to-face violence and bullying. It is crucial that we better understand the nature of all the risks children face and the likelihood that they might feel upset as a result of their exposure to such risks.

“Everyone started teasing and playing jokes on a boy. He ended up leaving the group.” (Boy, 13-14 years, Argentina)

“There are ugly comments about other people.” (Girl, 13-14 years, South Africa)

“Someone posts a status and starts insulting people. As we all share friends, they all get involved and make things worse in their comments … they will insult you, dare you to fight them.” (Girl, 13–14 years, Montenegro)

Up to a third of children report hurtful behaviour, most often offline

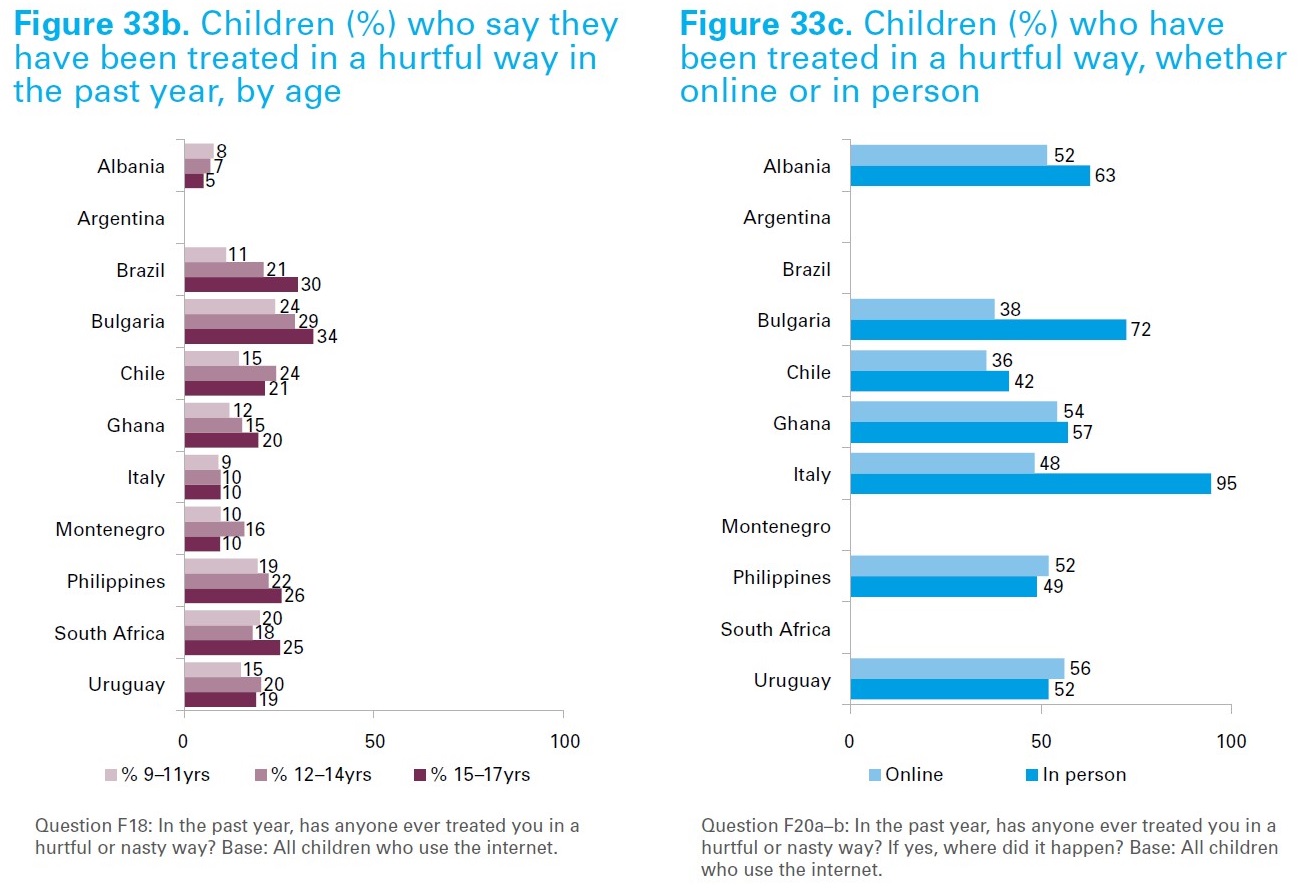

- Less than a third of children report that they have been treated in a hurtful way over the past year – either online or offline – according to the latest Global Kids Online comparative report. The proportion varies between 6% in Albania and 29% in Bulgaria which raises questions about cultures of childhood on- and offline and the need for a tailored approach.

- Being treated in a hurtful or nasty way is more common offline than online in five of the seven countries with data on this (Albania, Bulgaria, Chile, Ghana, Italy). Only in the Philippines and Uruguay, online hurtful behaviour is more common but the differences with the proportion of offline incidents are small.

- Older children are more likely to experience hurtful behaviour in most of the countries but in some contexts the early teens (12-14 year olds) are most exposed.

- In most countries (except Chile), fewer than one third of children had been exposed to something online in the past year that had upset them. The proportion varies between 9% (Italy) and 37% (Chile) of internet-using children aged 9–17 years.

Exposure to more risks makes harm more likely

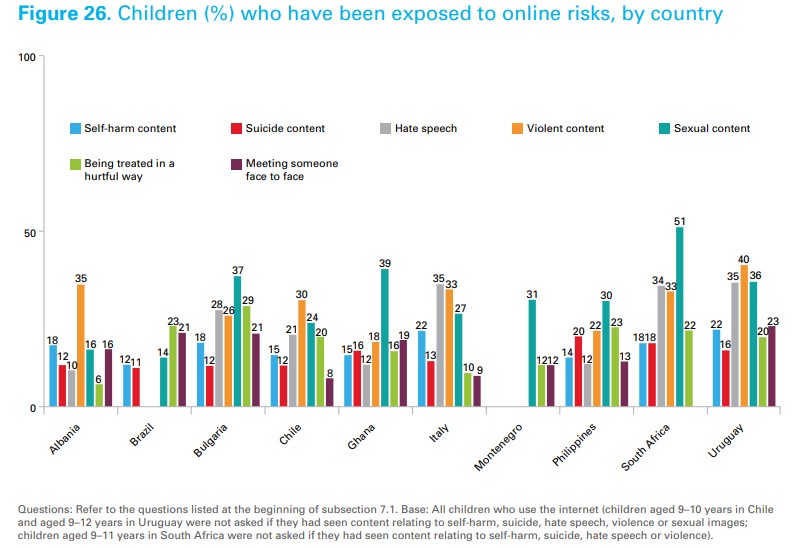

- A wide range of online experiences can be upsetting. Children were more likely to report being upset in the past year if they had encountered hate speech or sexual content online, been treated in a hurtful way online or offline, or met someone face to face that they had first got to know online. Exposure to more risks makes children more likely to experience harm.

- Being explicitly the target of aggression is not the only source of hurtful experiences, and more ‘passive’ forms, such as exclusion from a group or an activity, must be considered in relation to the online environment, as we suggest in a research paper on Recognising online hurtful behaviour among peers.

- Of the minority of children who report an online problem, a minority of incidents are either repeated or ‘fairly’/‘very’ upsetting. Still, this represents substantial numbers of children and so interventions are needed.

- Although hurtful online behaviour often happens only once or twice a year because of the very nature of the internet, it can remain online (even forever), and so may continue to be upsetting for longer. It is important to address any form of hurtful behaviour, not only repeated behaviour.

- The categories of ‘victim’ and ‘aggressor’ may overlap, especially as some victims may hit back as a response to hurtful behaviour and so become aggressors themselves.

The need for a balanced and integrated approach

A comprehensive approach to addressing hurtful behaviour is needed – one that focuses on collective cultures as well as individual bullying behaviour. Practical and policy responses should also recognise the interrelatedness of online and offline hurtful behaviours, and children’s active roles in both initiating hurtful experiences and offering peer support. This approach should also recognise the need for an early intervention and preventative focus.

Policy and governance approaches promoting internet use for children as a way of improving opportunities for education, communication and participation must recognise and address the fact that this also brings risks to children, including online hurtful peer behaviour, and work on educational initiatives to address this effectively. While the specific steps needed to advance children’s best interests may vary across countries, policy makers should take a balanced and integrated approach that aims to reduce children’s online exposure to harm without infringing their opportunities to benefit. Restrictive measures for protecting children from online risks of harm have clear drawbacks, as they reduce online opportunities and limit digital skills and may also miss the mark completely. Hence, states, schools, parents and children’s organizations around the world now face an urgent and important task– namely, to fulfil children’s rights in a digital world – in a way that both affords opportunities and limits harm.

More findings

The data cited and more results can be found in Growing up in a Connected World and Recognising online hurtful behaviour among peers.

Further resources

UNESCO – International day against violence and bullying at school including cyberbullying

Global Kids Online – research results and methodological tools

Post author: Mariya Stoilova